Credor Eichi Ⅱ,

taking the simple watch

to the highest peak

Photographs by Eiichi Okuyama

Text by Masayuki Hirota (Chronos-Japan)

Edited by Yuto Hosoda (Chronos-Japan)

The ultimate expression

of the skills brought together

at the Micro Artist Studio

The Eichi Ⅱ has made a name for itself

as a masterpiece among minimalist watches.

Its elaborate movement has been praised

many times over.

The reasons for this watch’s remarkable aura,

however, go well beyond

what’s on the inside.

The lapis lazuli blue porcelain dial,

born of trial and error,

and the case

that offers a view of the movement,

are among the other major elements

that go into making the Eichi Ⅱ

a masterful timepiece.

Eichi Ⅱ

The first edition of the Eichi Ⅱ came out in 2014.With the Eichi Ⅱ, the refinement that distinguished the original Eichi was raised to a new level. Cold forging was first applied to the case starting in 2018, enabling its surface to be more perfectly finished. Shown in the center is the lapis lazuli blue dial model, added in 2021 to commemorate the 140th anniversary of Seiko’s founding. Hand-wound Spring Drive movement (Caliber 7R14). 41 jewels. Power reserve of approximately 60 hours. 39 mm diameter, 10.3 mm thickness. Water resistant to 30 meters.

To this day, the Eichi Ⅱ remains a Credor watch longed for by people who appreciate excellent timepieces. The reasons go beyond the meticulously crafted movement. The unique quality of the case and the silky smooth finish of the porcelain dial set it apart from other luxury watches.

A lapis lazuli blue dial model (called the “Ruri Edition,” ruri meaning “lapis lazuli” in Japanese) was added to the Eichi Ⅱ series in 2021.Lapis lazuli is a gemstone that has been valued since ancient times for its deep blue color. Credor reproduced this color in a porcelain dial and adopted it in an Eichi Ⅱ model. Such a challenge could only have been taken on by the Micro Artist Studio, which is located in the Seiko Epson Shiojiri Factory, where the dials are made in house.

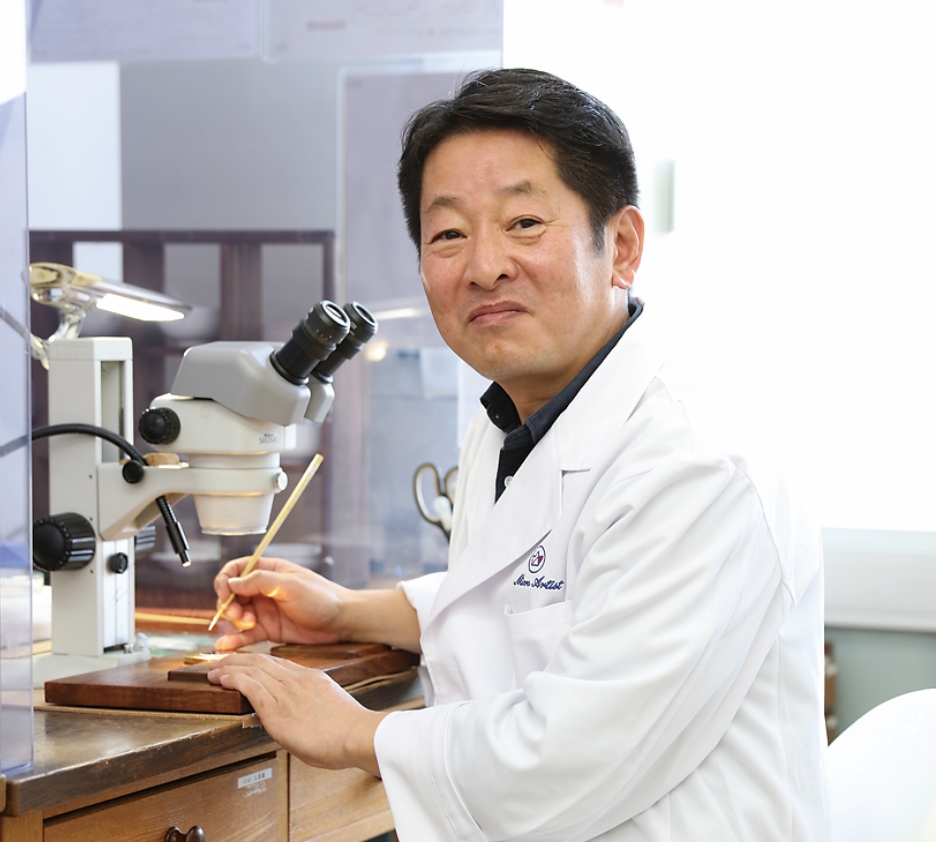

Let us look back at the timeline up to that accomplishment. The Eichi, announced in 2008, adopted a porcelain dial made by Noritake, the Nagoya-based firm known for its elegant porcelain tableware. In developing the Eichi Ⅱ, however, there was a desire to craft the watch in house to the greatest extent possible. To that end, Tetsuo Oguchi, in charge of decorative work at the Micro Artist Studio, acquired the skills for making the porcelain dial, learning how to paint on porcelain by attending classes at Noritake. The ceramic plate that is the base of the dial was found in Nagano Prefecture, home to the Micro Artist Studio, by exterior designer Noriaki Ozawa. What emerged eventually from a trial-and-error process was the Eichi Ⅱ, with an even more elaborately created porcelain dial.

In that a glass-like glaze is applied to the surface, a porcelain dial is the same as an enamel one. The only difference is the base material. An enamel dial is made on a metal base, whereas a porcelain dial has a ceramic base. Heating an enamel dial with its metal base would cause deformation, but it is readily affixed to the movement and less fragile than a porcelain dial. On the other hand, since a porcelain dial is not deformed by heating, it can withstand firing at higher temperatures. Affixing it to the movement, however, is difficult, and it is more susceptible to shock. Ozawa went looking for a supplier that manufactured very strong industrial ceramics, thereby achieving a porcelain dial for the Eichi Ⅱ with sufficient durability.

As previously mentioned, a porcelain dial can withstand firing at higher temperatures. The lapis lazuli blue dial added in 2021 can be seen as an attempt to capitalize on this advantage to the fullest extent. Applying a glass-like glaze and firing are the same as before. The processes, however, differ greatly.

There are generally two ways colors are applied to porcelain. One is the on-glaze method, layering pigments on top of the glaze. The other is the in-glaze method, melting the pigments into the glaze by firing them together. The former method is adopted for the indexes and logo of the Eichi dial, but Oguchi, who undertakes the painting of the dial for the Eichi Ⅱ, had a different wish in mind, “I wanted to try in-glaze, melting the pigments into the glaze.” The paints used with in-glaze are black or bluish hues. Oguchi went looking for paints and set about making the porcelain dial by the in-glaze method. The result was a deep blue dial that looked like lapis lazuli.

Ever since 2014, the white dial for the Eichi Ⅱ had been delivered as a ceramic base with a glaze applied to it. At the Micro Artist Studio, this is fired to make the glaze molten, and the indexes and other decorations are hand-painted on this molten glaze to produce the final product. In the case of the lapis lazuli blue dial, on the other hand, the work at the Micro Artist Studio starts with the glaze application process. The reason: “because what we want to do cannot be done by the supplier.” To achieve the aimed-for color, the craftspeople at the Micro Artist Studio go to extraordinary lengths.

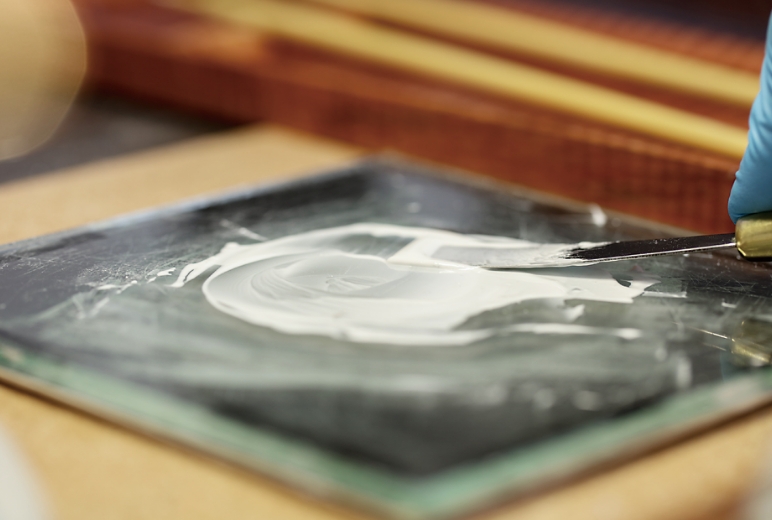

The standard way of obtaining a bluish glaze is to add pigments such as cobalt and manganese. But as more pigments are added to the mix so that the color becomes deeper, color uniformity may suffer. In fact, when Oguchi tried making a lapis lazuli dial with pigments of both blue and black hues, lumps of black pigment remained. How could he eliminate the black lumps and make the color uniform? He hit upon the approach of mixing the pigments and glaze medium, pulverizing the mix in a mortar, and straining through a mesh. Leaving only a fine powder after sieving, the lumps of pigment were gone and the color was more even.

Two kinds of pigments are used for the lapis lazuli blue dial. After repeated attempts, Oguchi finally arrived at the same hue as the blued screws used in the movement.

Firing is not a straightforward matter but requires special know-how. The temperature used for the in-glaze method is surprisingly high, around 1,200°C. This is much higher than the firing temperature of around 800°C when the indexes and logo are painted by the on-glaze method. Initially, firing at a lower temperature was tried; but after around 30 trial runs, the current conditions were settled on. A firing temperature of around 1,200°C is much higher than that for an ordinary enamel dial. One reason Oguchi was able to adopt the in-glaze method was that it was for a porcelain dial, which does not deform at high temperatures.

Ever since 2014, the white dial for the Eichi Ⅱ had been delivered as a ceramic base with a glaze applied to it. At the Micro Artist Studio, this is fired to make the glaze molten, and the indexes and other decorations are hand-painted on this molten glaze to produce the final product. In the case of the lapis lazuli blue dial, on the other hand, the work at the Micro Artist Studio starts with the glaze application process. The reason: “because what we want to do cannot be done by the supplier.” To achieve the aimed-for color, the craftspeople at the Micro Artist Studio go to extraordinary lengths.

The standard way of obtaining a bluish glaze is to add pigments such as cobalt and manganese. But as more pigments are added to the mix, so that the color becomes deeper, color uniformity may suffer. In fact, when Oguchi tried making a lapis lazuli dial with pigments of both blue and black hues, lumps of black pigment remained. How could he eliminate the black lumps and make the color uniform? He hit upon the approach of mixing the pigments and glaze medium, pulverizing the mix in a mortar, and straining through a mesh. Leaving only a fine powder after sieving, the lumps of pigment were gone and the color was more even.

Two kinds of pigments are used for the lapis lazuli blue dial. After repeated attempts, Oguchi finally arrived at the same hue as the blued screws used in the movement.

Firing is not a straightforward matter but requires special know-how. The temperature used for the in-glaze method is surprisingly high, around 1,200°C. This is much higher than the firing temperature of around 800°C when the indexes and logo are painted by the on-glaze method. Initially, firing at a lower temperature was tried; but after around 30 trial runs, the current conditions were settled on. A firing temperature of around 1,200°C is much higher than that for an ordinary enamel dial. One reason Oguchi was able to adopt the in-glaze method was that it was for a porcelain dial, which does not deform at high temperatures.

When viewed closely, a porcelain dial made by applying a glass-like glaze and firing has a slight bulge at its center, gradually declining toward the periphery. This is due to the surface tension of the melted glassy glaze. The same is true of the white dial, but it is more pronounced with the lapis lazuli blue dial. The effect is that the outer circumference, with the white undercoat barely showing through, gives the dial a subtly nuanced appearance. Needless to say, this was the aim. “With the lapis lazuli blue dial, we wanted to make the outer circumference stand out more,” said Oguchi. “Depending on the firing conditions, however, there is a danger of the glaze becoming uneven, affecting the roundness of the outer circumference. We took these factors into account when deciding the firing time and temperature.”

From the dial manufacturing process

The raised glaze on the Eichi Ⅱ dial creates an original look. The nuance not found in rival watches is once again a result of the porcelain. As noted earlier, if an enamel dial were to be fired at around 1,200°C, it would be deformed by the high temperature. While this can be corrected by pounding the dial flat when cooling it, the rise at the center of the glaze would be sacrificed. With porcelain, however, which is impervious to such deformation, there is no need to correct the dial. This is the main reason for the success in achieving the elegant rise of the glaze on the Eichi Ⅱ dial.

After the glaze binds to the ceramic base at around 1,200°C, the next step is polishing. The glassy glaze that has been raised by surface tension is carefully polished, thereby completing the dial with the silky smooth finish for which the Eichi series is known. Looking at the Eichi series dials, however, all the polishing traces that can be seen on an industrial enamel dial are gone. “The polishing method used for the white dial, if used for the lapis lazuli blue dial, leaves noticeable scratches,” Oguchi explains.

- Dial before firing

- Dial after firing

A glaze raised by surface tension could not have been possible without a ceramic base that is certain not to deform. What’s more, the in-glaze method, in which the pigments are melted into the glaze during firing, obtains a unique depth different from an enamel dial. Thanks to the effect of surface tension on the glaze during firing, the thickness of the glaze becomes thinner on the periphery, creating a unique nuanced effect. Today, when many watchmakers are engaged in manufacturing enamel dials, Seiko Epson with its Micro Artist Studio is one of the few making porcelain dials with glaze applied.

Is there a material that can better polish a glass-like glaze? Taking a hint from the polishing process used for eyeglass lenses, after being introduced to a certain company, he obtained an abrasive unlike any in use in watches before then. Even when viewing the dial under a magnifying glass, there are no polishing traces to be seen whatsoever. No matter how skillfully the glaze is applied or how finely the particles are filtered, however, there is the problem of tiny bubbles forming in the glaze. That is why the surface is polished after firing many times: to get rid of all the bubbles. Working with the white dial up to now was itself a painstaking effort, but manufacturing the lapis lazuli blue dial is an even more exacting task.

The uniqueness of the Eichi Ⅱ is not limited to the dial. The movement, as viewed from the case back side, appears as though it is floating in the air. The deep beveling on the periphery of the movement holder is therefore emphasized. The reason is the unique method by which the movement is held in place.

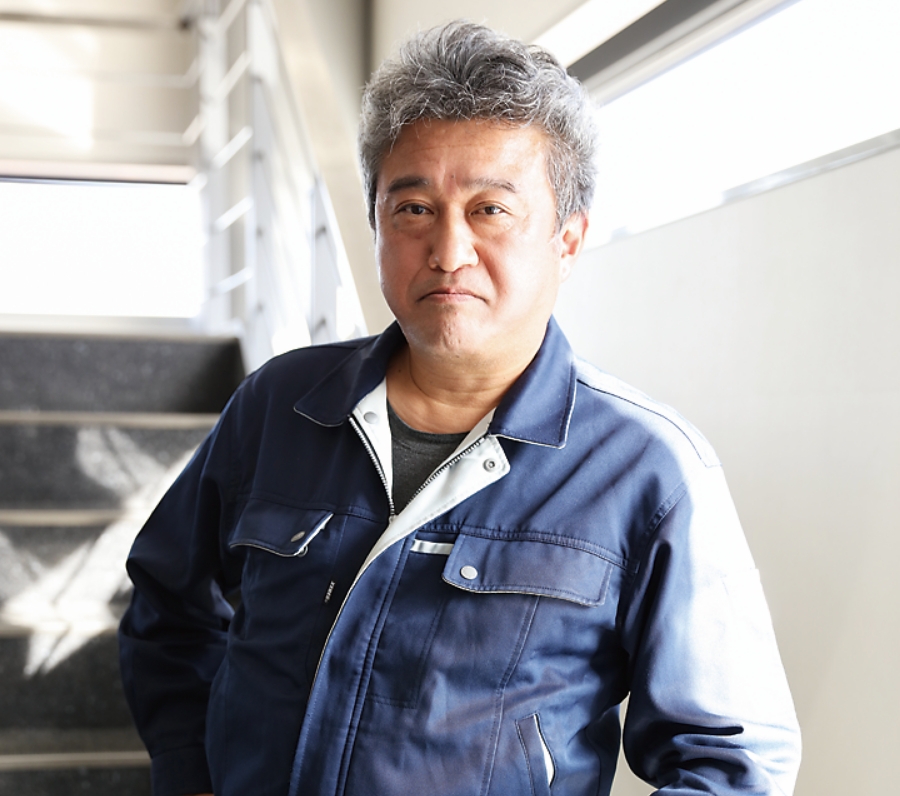

Ordinarily, a spacer is inserted in the case and the movement is attached there. The Eichi Ⅱ, on the other hand, has protrusions on the inner side of the case; and this is where the movement is attached. One reason is that a large movement is made to fit in a small case.

This also results in a lighter case for greater wearing comfort. Another reason is that the case back’s outer edge is made narrow for a larger appearance, so that the beveling on the movement periphery will be fully visible through the case back glass. While not a few watchmakers pour ingenuity into the casing process, attempts like this to make the entire movement visible are much rarer.

One of the major reasons a porcelain dial could be adopted for the Eichi Ⅱ is this outstanding case. Since a porcelain dial cannot be supported from behind by legs, the only way to support it is to fit it tightly inside the case. Since the dial itself, however, lacks the flexibility of a metallic material, a strong shock might break it.

With the Eichi Ⅱ, the porcelain dial is secured by a pure iron dial rim and goes under the bezel. In this process, by leaving a 0.1 mm clearance between the dial and case, the dial will not come in contact with the bezel even if the watch receives a shock. In fact, of all the requests for repair received by Micro Artist Studio for the Eichi and Eichi Ⅱ, not one has involved breakage of the dial.

There are slight differences, however, in the thickness of porcelain dials applied with glaze. Because of this, even when assembled in the same way, the clearance obtained may not always be exactly 0.1 mm. With the Eichi Ⅱ, therefore, three kinds of case clamps are used, differing in their thickness by 0.05 mm each, to fix the movement to the case. If the dial is thick, the clearance with the bezel will be narrow; but a 0.1 mm clearance can still be obtained by using thinner case clamps.

The idea of interchanging case clamps depending on the dial thickness is certainly a new one, unheard of before. It is just such a level of dedication, though, that has made this watch become desired by enthusiasts around the world. The words of Michelangelo seem appropriate when talking about the Eichi Ⅱ, where careful attention has been paid to every last detail. “Trifles make perfection, but perfection is no trifle.”